Bats: General Characteristics and Classification

Bats are small mammals capable of true sustained flight.

They belong to the second-largest mammalian order, Chiroptera (order

of mammals adapted for flight), which comprises 22% (over 1400) of all

mammalian species after rodents. They are found on all continents except

Antarctica. Bats are divided into two types: Megachiroptera (fruit

bats that rely mainly on vision), which fly by vision, and Microchiroptera

(insectivorous bats), which fly by echolocation (biological

sonar using sound waves) and magnetoreception (ability to sense

Earth’s magnetic field).

Habitat, Ecology, and Ecological Importance of Bats

Most bats live in caves, hollow trees, and foliage, in large

colonies of 100 to 100,000 individuals. Because of their feeding practices on

insects, fruits, nectar, pollen, fish, etc., they are extremely important for

the ecosystem, for pollination and pest control. Without bats, numerous

medicinal plants would vanish.

Unique Biological Features of Bats

Bats are rather unique mammals. Their ability to harbor

viruses comes from various traits within themselves. A few of those traits are

as follows:

• Bats can fly up to 2000 km, depending on the species, in

their immense migration movements.

• During their flight, bats are metabolically active with

their body temperature rising to about 41°C, with 1066 beats per minute and up

to 34 times basal metabolic rate owing to energy consumption.

• Because of this reason, the nocturnal mammals sleep and

hibernate occasionally, during which their heart beats become 10 to 16 beats

per minute, with the body temperature being less than 5.8°C.

• Similarly, despite their smaller body size ratio, they are

the second most common living mammal, living up to 40 years.

Bats as Viral Host Reservoirs

The idea of viruses being in bats was formulated in the

early 20th century with the discovery of the rabies virus (neurotropic

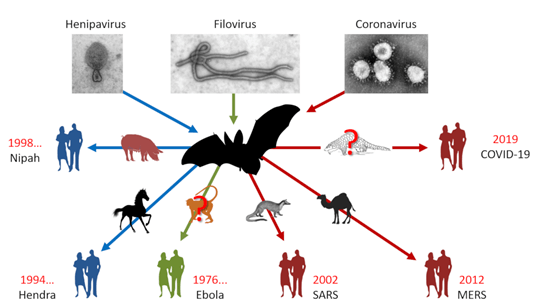

RNA virus) in bats. Since then, about 54% of zoonotic viral pathogens

(viruses transmitted from animals to humans) have been discovered in

these small creatures. A few of the significant bat-borne viruses are SARS,

MERS, Ebola, Hendra, Nipah, etc. These viruses are responsible for respiratory

diseases, diarrhea, pneumonia, bronchitis, the common cold, and other diseases.

Coronaviruses (enveloped RNA viruses) like SARS-CoV-2

(virus causing COVID-19) are asymptomatic in bats, unlike in civets and

pangolins. However, they are not entirely immune to all illnesses. To

elaborate, a few viruses, such as Tacaribe virus (arenavirus) and

Lyssavirus (rabies-related virus), can cause severe symptoms in

bats, even leading to death.

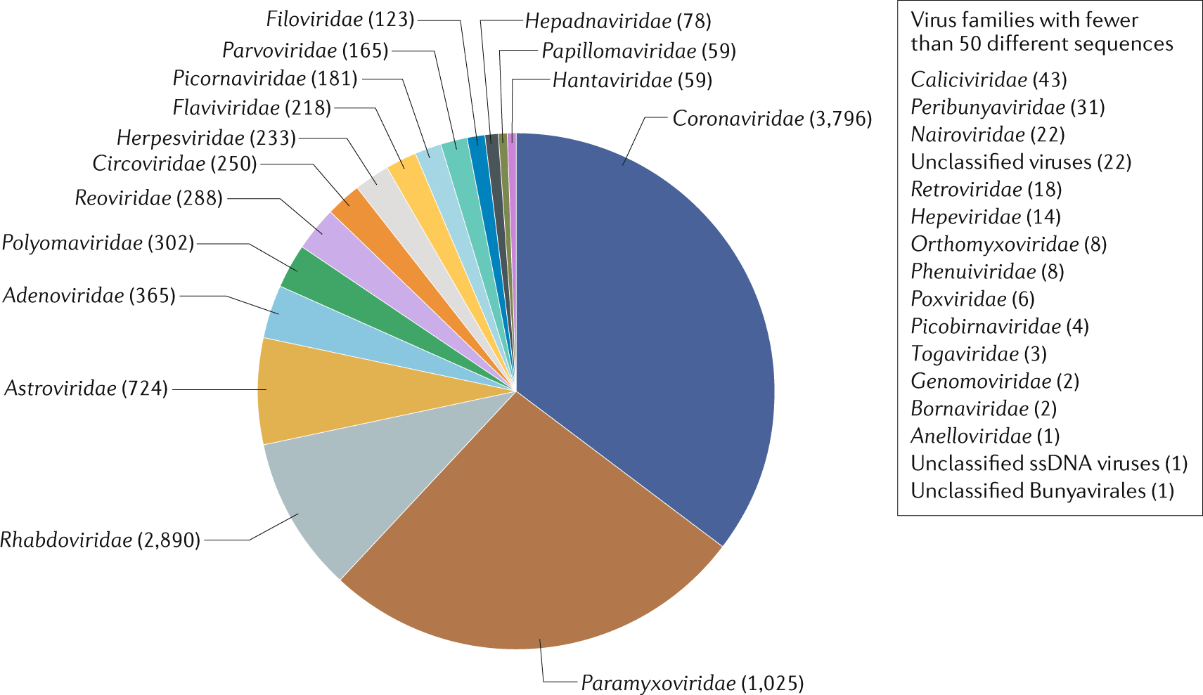

Figure: Diversity of Zoonotic viruses in bats. Source:

Irving et al., 2021.

Coevolution of Bats and Viruses

The abundance of viruses in bats calls for their

relationship to be rooted deep within their genome, relating to evolution.

Fossil evidence suggests that bats and viruses go way back to more than 65

million years during the extinction of dinosaurs, i.e., the KT extinction

event (Cretaceous–Tertiary mass extinction). Studies have revealed

that bats have an abundance of RNA viruses (viruses with RNA genomes)

rather than DNA viruses (viruses with DNA genomes).

This might be because RNA viruses are more prone to errors

because of the lack of a proofreading mechanism (error correction

during replication) in RNA polymerase (enzyme that synthesizes

RNA), in contrast to DNA polymerase (enzyme that synthesizes DNA)

in DNA viruses. This leads to more variability in the antigen receptor (viral

structure recognized by the immune system) of the virus, which enhances its

viral capabilities to infect the host.

Figure: Zoonotic Transmission of Virus from Bats. Source:

Gérald, 2020.

Bat Immunity Against Viruses

Several hypotheses exist regarding why bats harbor a

considerable number of viruses. Since the discovery of viral pathogens in bats,

the fever hypothesis (idea that elevated body temperature limits

viral replication) has been thought to be the major assumption for bat

immunity.

When the body gets infected by a certain pathogen, its

primary defense mechanism is to raise temperature, to cause fever. The body

increases its temperature to a suboptimal level to kill the unwanted

pathogen/s. Bats innately have rising body temperatures of up to 41°C during

their flight. According to the fever hypothesis, this is thought to decrease

viral load and minimize infection. However, research has suggested that no

viral titer variability was found in bat cells grown at 37°C and 41°C, meaning that

the number of virus counts was similar in both cases. The hypothesis, however,

cannot be fully discarded as it might have some kind of relationship with other

aspects of bat immunity.

Innate Defense Mechanisms in Bats

• Interferon Expression: Type I Interferons (IFNs)

(antiviral cytokines) are cytokines or signaling proteins that help the

body fight against infections. In humans, IFNs are inducible after infection.

The same is not true for bats; bats constitutively express IFNs even before

stimulation with enhanced viral response. These genes are regulated by IFN

regulatory factors (transcription factors controlling IFN genes),

lowering the production of inflammatory cytokines. Similarly, IFN-stimulated

genes (ISGs) (genes activated by interferons) also play a role in

maintaining viral titer in bats without showing any sign of clinical symptoms.

• Heat shock proteins (HSPs) (molecular chaperones

that protect proteins) are produced in enhanced levels in bats and tolerate

high temperature and oxidative stress during flight. This may account for the

rapid evolution of the virus, which tolerates mutations through the use of

chaperone viral proteins.

• Enhanced autophagy (cellular recycling and

pathogen removal mechanism) is well developed in bats and helps in removing

pathogens.

Immune Tolerance Mechanisms in Bats

The most significant immune tolerance mechanisms in bats are

the variation in the cGAS–STING pathway (DNA sensing innate immune

pathway) and the NLRP3 inflammasome pathway (inflammatory

cytokine activation pathway).

cGAS–STING Pathway

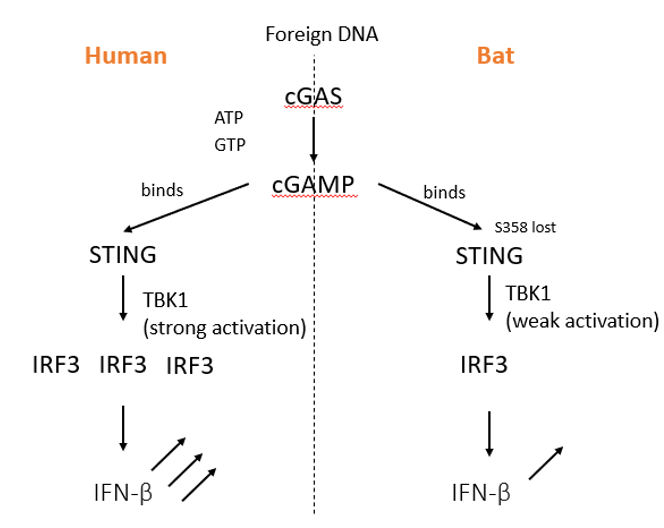

The cGAS–STING pathway is a component of the immune

system that functions to determine the presence of cytosolic DNA to trigger the

expression of inflammatory genes. Foreign or abnormal DNA is initially detected

by cGAS (cyclic GMP-AMP synthase) (DNA sensor enzyme). The cGAS

binds to the DNA and leads to the formation of cGAMP (second

messenger molecule). The produced cGAMP binds to STING (Stimulator of

Interferon Genes) (adapter protein) and activates it. This

activation leads to signaling events involving TBK1 (kinase) and IRF3

(transcription factor), resulting in IFN production.

In bats, however, the STING-dependent IFN response is weak

due to a point mutation in the STING protein, inducing weak TBK1 response and

leading to lower production of IFN.

Figure: Comparison between the cGAS–STING Pathway in

Humans and Bats.

NLRP3 Inflammasome Pathway

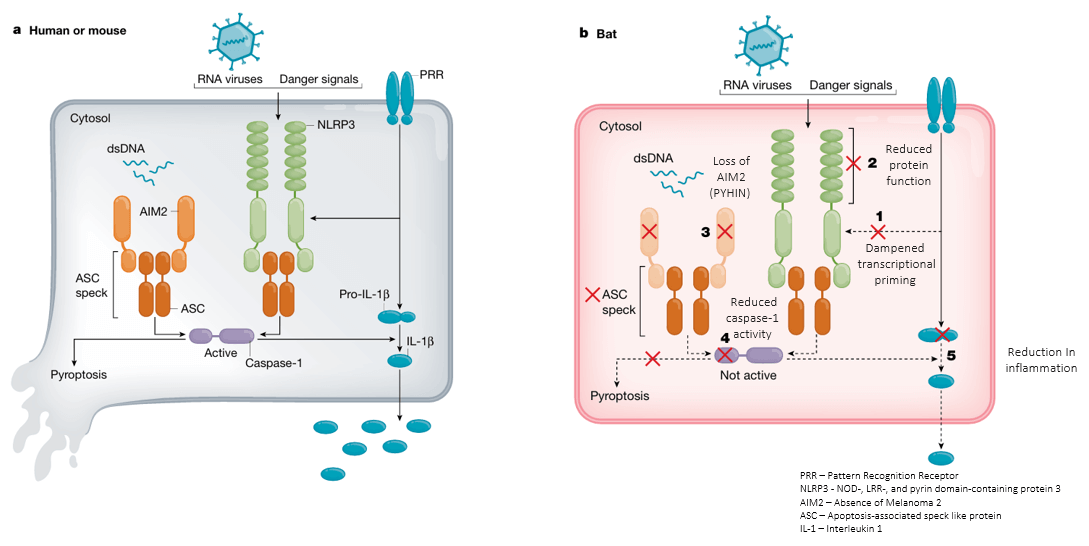

The NLRP3 inflammasome pathway regulates the innate

immune system and inflammatory cytokines.

In humans or mice, the pathway involves activation of NF-κB

signaling (transcription factor pathway) via Pattern Recognition

Receptors (PRRs) (pathogen sensors), leading to expression of pro-IL-1β

and NLRP3. The ASC protein (adaptor protein) recruits caspase-1

(protease enzyme), which cleaves pro-IL-1β to IL-1β, inducing

inflammation and pyroptosis (inflammatory cell death).

In bats, the inflammasome pathway is diminished. PRR

activation abnormally activates NLRP3, leading to reduced protein function.

Loss of AIM2 protein (DNA sensor of PYHIN family) impairs ASC

complex formation, resulting in reduced caspase-1 activation. Therefore,

pyroptosis is absent and IL-1β production is lowered, significantly reducing

inflammation.

Figure: Comparison between the NLRP3 Inflammasome pathway in Human/mouse and Bat. Source: Irving et al., 2021.

Spillover in Bats

• Roosting habitat: Bats innately have a dirty

roosting habitat where thousands of bats reside in a single cave. They often

excrete, which becomes a grooming area for zoonotic pathogens (pathogens

transmitted from animals to humans). The pathogens can also spread easily

within the colony.

• Physiological stress: When bats are stressed by

certain stimuli, which can include low food availability or a predator, their

behavior becomes abnormal. This leads to reduced immune function, more

susceptibility to pathogens, and negatively affects reproductive physiology

(biological processes related to reproduction).

• Environmental changes: Climate change (long-term

alteration of temperature and weather patterns) affects the physiology of

the ecosystem. Bats must travel large distances to feed on insects, fruits,

nectar, etc., which is not optimal. Similarly, urbanization (expansion

of human settlements) disturbs bat habitats, therefore promoting viral

spillover.

• Direct human exposure: Direct human exposure to

bats is rare. In some parts of the world, humans hunt bats for illegal wildlife

trading and even consume them. Bat excreta, known as bat guano (nitrogen-rich

bat feces), is also a valuable fertilizer because of its rich nitrogen

content. The extraction of this compound can expose humans to bats, leading to zoonotic

transmission (animal-to-human disease spread).

• Bridging host exposure: Bridging host exposure is

more common when an intermediate host (animal transmitting pathogens

between species) directly contacts bats, and then the pathogen is

transmitted to humans. This is exemplified by the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic,

where civets or pangolins were proposed to be infected through bats and

subsequently transmitted the virus to humans.

Learning from Bats

• Immune tolerance: Bats have developed several

mechanisms to combat zoonotic viral pathogens and inflammatory diseases.

Studies on these mechanisms can be helpful in developing cures for autoimmune

diseases (conditions where the immune system attacks self tissues)

or combating viral infections.

• Viral spillovers: Research on viral spillovers from

bats or other zoonoses (diseases transmitted from animals to humans)

helps prevent and predict potential epidemics and pandemics in the future.

• Model species: Like mouse, zebrafish (vertebrate

genetic model), Drosophila (fruit fly genetic model), bats

have high potential to be powerful model species (organisms used to

study biological processes) to study zoonotic hosts. Bat-mouse chimera

models (organisms containing cells from two species) and mouse

models with bat genes are being developed to study zoonotic host–pathogen

dynamics.

• Disturbance of bat habitats: Because of bat habitat

characteristics and their association with multiple diseases, it is wise to

avoid contact with bats or disturbance of their populations.

Challenges in Bat Research

• In vivo challenges: In vivo research (experiments

conducted in living organisms) is essential to fully understand bats and

their physiology. This requires captivity of bats, which is extremely

challenging due to their nocturnal behavior, flight ability, and mysterious

lifestyle. Extensive safety measures and care are required.

• In vitro challenges: In vitro research (experiments

conducted outside living organisms) is an alternative approach. Culturing

bat cells in laboratory conditions is developing but remains in a novice stage.

This requires bat-specific tools, reagents, and antibodies. Due to differences

in bat immunity compared to humans and mice, appropriate immunological

reagents (tools used to study immune responses) are limited.

• Larger species diversity: Because of extensive species diversity (variety of species within a group) in bats, identifying a consensus bat species for research is difficult. Findings in one bat species may not apply to others.