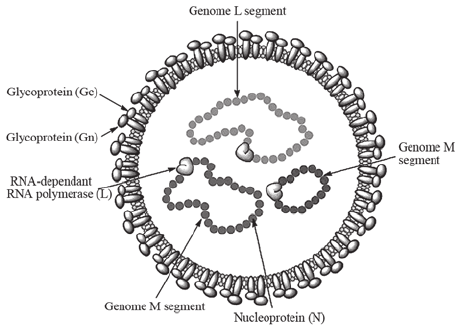

Structure of Crimean-Congo Hemorrhagic Fever Virus

- Crimean-Congo

hemorrhagic fever virus (– causative agent of CCHF) falls under

the family Bunyaviridae (– family of segmented RNA viruses)

and genus Nairovirus (– tick-borne bunyaviruses).

- They

are spherical particles (– round virus particles) measuring 90

to 120 nm (– nanometer size range) in diameter with 5–10 nm

projections (– surface spikes) visible on the surface.

- They

are an enveloped virus (– surrounded by lipid membrane)

which comprises two glycoproteins (G1 and G2) (– viral surface

proteins involved in attachment and fusion).

- The

genome is tripartite (– divided into three segments), negative-sense

RNA (– RNA complementary to mRNA), termed the large (L),

medium (M), and small (S) segments, which are associated with protein

to form nucleocapsids (– RNA–protein complexes).

- The nucleocapsid

(– viral genome plus proteins) is surrounded by a lipid-containing

envelope (– outer viral membrane).

- The

nucleocapsids include the RNA-dependent RNA polymerase (L protein)

(– enzyme that synthesizes viral RNA).

Figure: Crimean-Congo hemorrhagic fever virus structure.

Source: DOI: 10.3892/br.2015.545

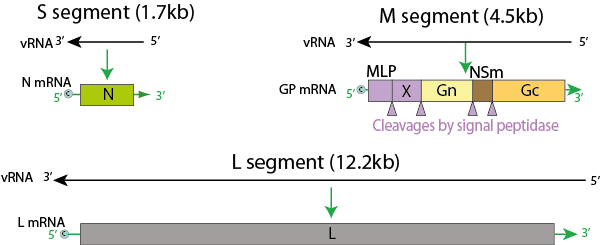

Genome of Crimean-Congo Hemorrhagic Fever Virus

- The

genome is linear, tripartite, segmented negative-stranded

RNA (– linear RNA genome with three segments of negative polarity).

- It

comprises three segments (– genome divisions): large (L),

medium (M), and small (S).

- The L

segment is 12,164 nucleotides, the M segment is 4,888

nucleotides, and the S segment is 1,712 nucleotides (–

segment lengths).

- It

encodes four to six proteins (– viral structural and functional

proteins).

- Terminal

complementary nucleotide sequences (– matching RNA ends) are

conserved on the L, M, and S segments (– conserved genomic

regions).

- The S

segment of nairoviruses encodes only a large N protein (–

nucleoprotein that binds RNA) and has no known nonstructural

protein coding information (– lacks accessory proteins).

- The M

segment of the nairovirus seems to encode only G2 and G1 (–

envelope glycoproteins).

- Nucleotide

sequencing (– determining RNA sequence) of the L RNA of

Crimean-Congo hemorrhagic fever virus revealed that the segment is 12,164

nucleotides in length and encodes 3,944 amino acids (–

protein length).

- The viral

RNA-dependent RNA polymerase (L) (– viral transcription enzyme)

binds to a promoter (– transcription initiation site) on

each encapsidated segment (– RNA coated with protein) and transcribes

the mRNA (– messenger RNA synthesis).

- These

mRNAs are capped (– addition of 5′ cap) by the L protein

during synthesis using cap-snatching (– stealing caps from host

mRNA).

Figure: Genome of Nairovirus, Source: Viral Zone

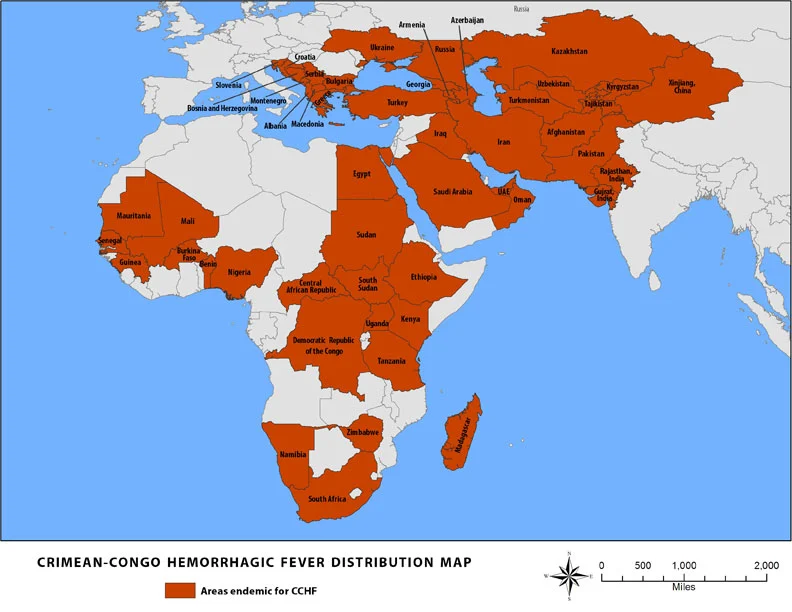

Epidemiology of Crimean-Congo Hemorrhagic Fever Virus

- Crimean-Congo

hemorrhagic fever (CCHF) virus, of the Nairovirus genus (–

tick-borne virus group), was first recognized in the Crimean

peninsula (– region in southern Ukraine) during an outbreak of hemorrhagic

fever (– bleeding fever) among agricultural workers (–

occupational exposure).

- The

same virus was isolated in 1956 from a single patient in the

present-day Democratic Republic of Congo, leading to the actual naming

(– Crimean + Congo).

- Although

animals and humans (– multiple hosts) can be infected, only

the latter (– humans) develop the disease.

- Crimean-Congo

hemorrhagic fever is a tick-transmitted viral disease (–

arthropod-borne infection) found in Bulgaria, Yugoslavia, the

former Soviet Union, China, Iraq, United Arab Emirates, Pakistan, and

sub-Saharan Africa.

- The vector

tick (– transmitting arthropod) is usually of the Hyalomma

(– hard tick genus).

Source: CDC, 2014

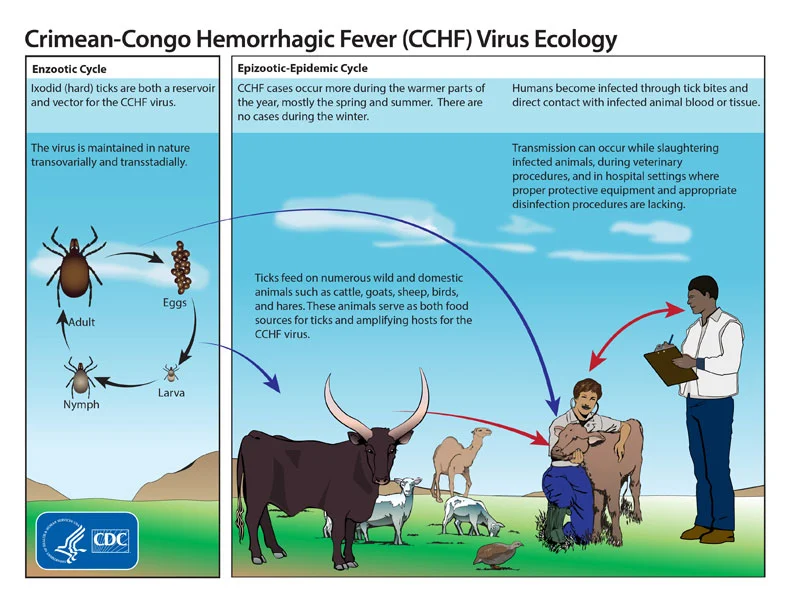

Transmission of Crimean-Congo Hemorrhagic Fever Virus

- Ixodid

ticks (– blood-sucking arthropods) especially those of the

genus Hyalomma (– tick genus), are both a reservoir (–

organism that harbors virus) and a vector (– transmitter of

virus) for the CCHF virus (– Crimean-Congo hemorrhagic fever

virus).

- Transmission

to humans occurs through contact with infected ticks or animal

blood (– viremic livestock blood).

- CCHF

can be transmitted from one infected human to another by contact with infectious

blood or body fluids (– secretions capable of transmission).

- Improper

sterilization of medical equipment, reuse of injection needles,

and contamination of medical supplies (– hospital-acquired

exposure) can result in spread of CCHF in hospital premises.

Figure: Life cycle of the Crimean-Congo hemorrhagic fever

virus, Source: CDC

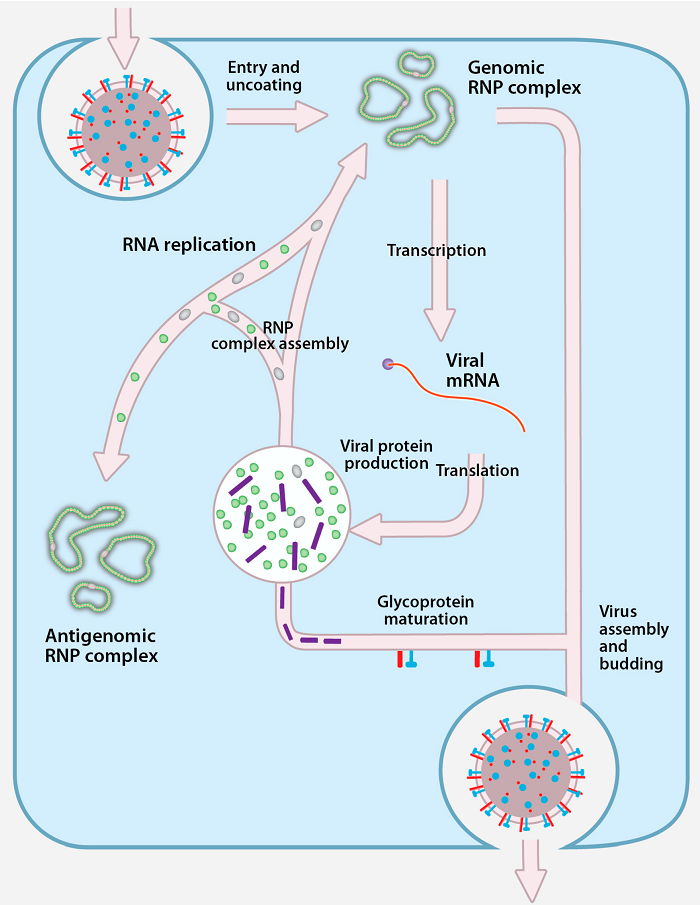

Replication of Crimean-Congo Hemorrhagic Fever Virus

- Virus

attaches to host receptors (– cell surface binding sites)

through glycoprotein (– viral attachment protein) and is endocytosed

(– internalized) into vesicles in the host cell.

- Fusion

of virus membrane with the vesicle membrane results in the

release of the ribonucleocapsid (– RNA–protein complex) into

the cytoplasm (– intracellular fluid).

- The RNA-dependent

RNA polymerase (RdRp) (– enzyme synthesizing RNA from RNA)

complex initiates transcription (– viral mRNA synthesis) by

binding to the leader sequence (– regulatory RNA region) at

the 3′ end of the genomic negative-strand RNA, and viral mRNAs

(– messenger RNAs) are capped in the cytoplasm.

- During

replication (– genome copying), the RNA-dependent RNA

polymerase complex binds to the leader sequence on the encapsidated

(-)RNA genome (– protein-coated RNA) and starts replication.

- The antigenome

(– complementary RNA strand) is concomitantly encapsidated (–

coated with nucleoproteins) during replication and replicates to give

rise to negative-sense genome (– infectious RNA strand).

- Nucleocapsids

(– RNA-protein assemblies) assembled induce formation of membrane

curvature (– bending of host membrane) in the host cell

membrane and wrap up in the forming bud at the Golgi apparatus (–

cellular protein-sorting organelle), releasing the enveloped virion

(– lipid-coated virus) by exocytosis (– vesicle-mediated

release).

Figure: Replication of Crimean-Congo Hemorrhagic Fever

Virus, Source: doi:10.3390/v8040106

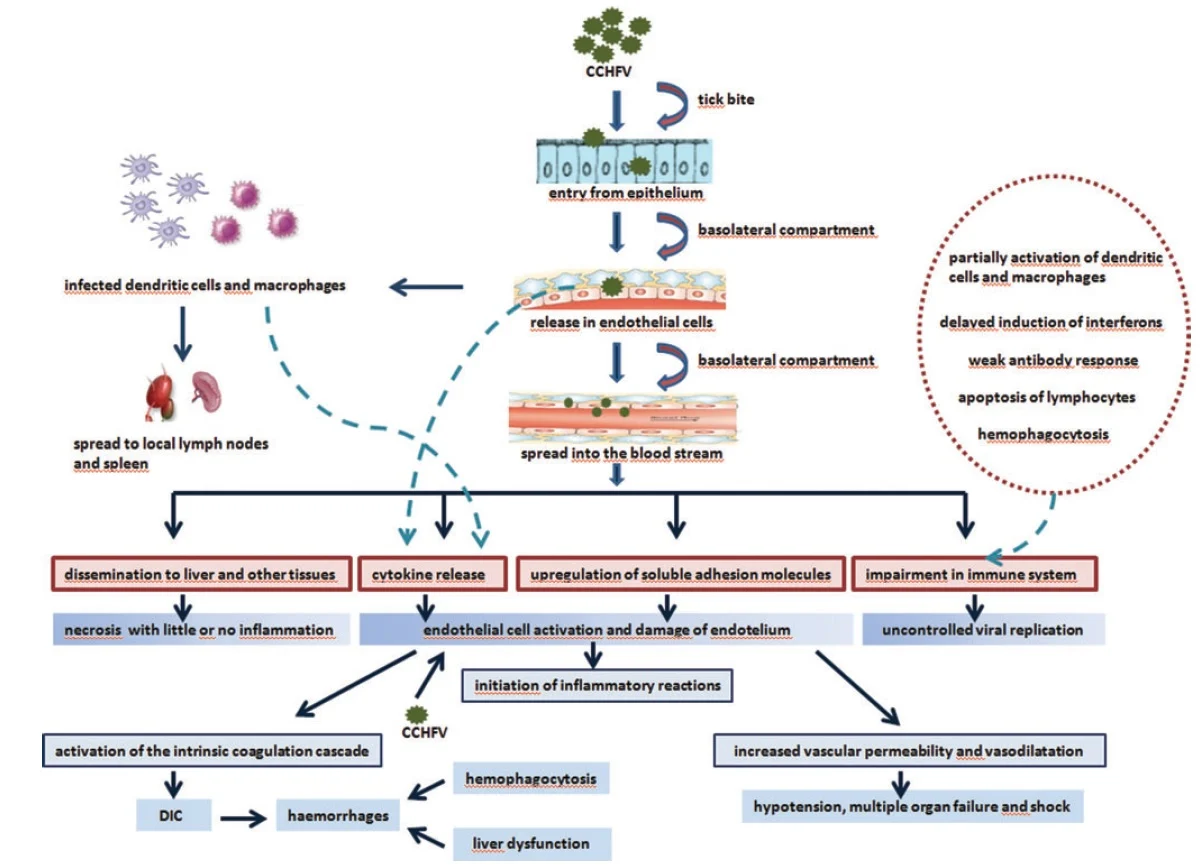

Pathogenesis of Crimean-Congo Hemorrhagic Fever

- The gut

of the vector (– tick digestive tract) is infected initially,

and after a few days or weeks the virus appears in the saliva (–

infectious secretions).

- When

the vector takes a blood meal (– feeding on host blood), the

infective saliva enters the small capillaries (– tiny

blood vessels) or lymphatics (– lymph vessels) of the

human or other vertebrate host (– animal with backbone).

- An incubation

period (– time before symptoms) of a few days ensues, after

which the vertebrate host develops viremia (– virus present in

blood).

- The

host becomes febrile (– develops fever), manifesting the

more serious signs and symptoms characteristic of the infecting virus.

- A typical humoral immune response (– antibody-mediated immunity) leads to cessation of viremia and clinical recovery in most cases, with immunoglobulin M (IgM) (– early antibody) predominating initially, followed by immunoglobulin G (IgG) (– long-term antibody), and the host recovers unless a specific target organ (– organ preferentially damaged) is affected.

- The

target organ is the liver (– metabolic organ) and vascular

endothelium (– inner lining of blood vessels) in Crimean-Congo

hemorrhagic fever.

- This

further leads to hemostatic failure (– inability to stop

bleeding) by stimulating platelet aggregation and degranulation

(– platelet activation), with subsequent activation of the intrinsic

coagulation cascade (– clotting pathway).

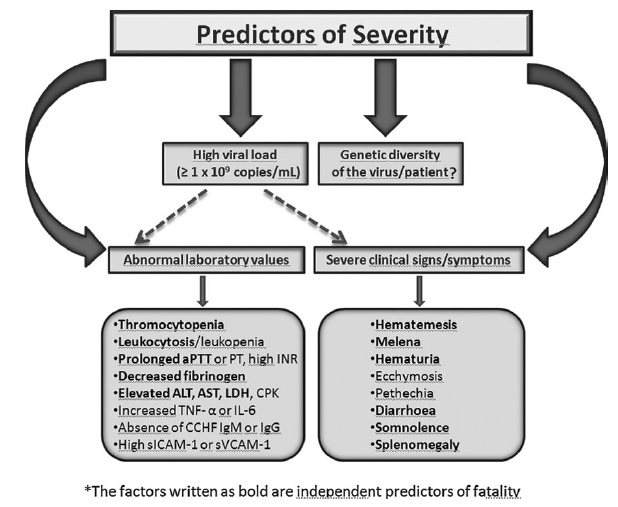

- Proinflammatory

cytokines (– immune signaling molecules) are key regulators in

the pathogenesis and mortality of patients with CCHF.

- Levels

of Interleukin-6 (IL-6) (– inflammatory cytokine) and Tumor

Necrosis Factor-α (TNF-α) (– major inflammatory mediator) are

significantly higher in patients with fatal CCHF.

Clinical Manifestations of Crimean-Congo Hemorrhagic Fever

- Following

an incubation period of 3–21 days, a non-specific febrile

illness (– fever with general symptoms) of abrupt onset

develops.

- Initial

signs and symptoms include headache, high fever, back

pain, joint pain, stomach pain, nausea, and non-bloody

diarrhea.

- Red

eyes, flushed face, red throat, and petechiae (–

small red hemorrhagic spots) on the palate are common.

- This

is accompanied by hypotension (– low blood pressure), relative

bradycardia (– slow heart rate), tachypnea (– rapid

breathing), conjunctivitis (– eye inflammation), pharyngitis

(– throat inflammation), and cutaneous flushing or rash (–

skin redness).

- Symptoms

may also include jaundice (– yellowing due to liver damage),

and in severe cases, changes in mood and sensory perception

(– neurological involvement).

- The hemorrhagic phase (– bleeding stage) is generally short and has a rapid course with signs of progressive hemorrhage and diathesis (– bleeding tendency) including petechiae, conjunctival hemorrhage, epistaxis (– nose bleed), hematemesis (– blood in vomit), hemoptysis (– coughing blood), and melena (– black stools).

- Internal

bleeding, including retroperitoneal (– abdominal cavity)

and intracranial hemorrhage (– bleeding in brain), may

occur.

- Hepatosplenomegaly

(– enlarged liver and spleen) may be present, and in severe cases

death occurs due to multiorgan failure, disseminated

intravascular coagulation (DIC) (– widespread clotting), and circulatory

shock (– failure of blood circulation).

Diagnosis of Crimean-Congo Hemorrhagic Fever Virus

- Virus

isolation by intracranial inoculation of suckling mice (–

sensitive animal model) is thought to be the most sensitive system

available; however, several sensitive cell culture systems (–

virus-growing cells) such as Vero, LLC-MK2, and BHK-21

cell lines are available.

- Immunohistochemical

staining (– antibody-based tissue staining) can show evidence

of viral antigen in formalin-fixed tissues (– preserved

specimens).

- Detection

of antibodies (IgG and IgM) (– immune response markers) by ELISA

(– enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay).

- Detection

of viral antigen, viral RNA sequence by RT-PCR (–

molecular RNA detection), in blood or tissues collected from a fatal

case, and virus isolation.

Treatment of Crimean-Congo Hemorrhagic Fever

- Supportive

treatment (– symptom-based care) including fluid balance,

correction of electrolyte abnormalities, oxygenation, and hemodynamic

support (– blood pressure maintenance).

- The

virus is sensitive in vitro (– laboratory conditions) to the

antiviral drug ribavirin, which is administered in both IV and

oral forms (– injection and tablets) with apparent benefit.

Prevention and Control of Crimean-Congo Hemorrhagic Fever Virus

- There

is no safe and effective vaccine currently available for human use.

- In

case of known direct contact with blood or secretions (–

exposure risk) of a probable or confirmed case, such as needlestick

injury (– sharp injury) or contact with mucous membranes

(– eye or mouth), baseline blood studies should be carried out and oral

ribavirin started as post-exposure prophylaxis (– prevention

after exposure).

- Use

of insect repellent on exposed skin and clothing.

- Wearing

gloves and other protective clothing (– barrier protection).

- Avoiding

contact with blood and body fluids of livestock or humans showing

symptoms of infection.

- Use of proper infection control precautions (– hospital safety measures) to prevent occupational exposure (– workplace infection risk).